RSA by example

It’s weirdly easy to create an RSA key without relying on a crypto library, you shouldn’t do that for any actual production use case but here are all the pieces you need to achieve it.

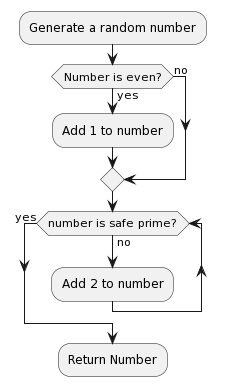

OK the first step of RSA is you have to pick two large prime numbers. We need to make sure those numbers are unpredictable so we should do the following process:

We can get random numbers from Linux’s /dev/urandom which uses noise from disk i/o operatioons, keyboard and mouse movements, and other system activities that are hard to predict. It then uses a hash function to smooth the randomness. You can determine if a number is a prime number by using the Miller–Rabin primality test which looks like this in python:

import random

def miller_rabin(n, k=40):

"""

Perform the Miller-Rabin primality test.

Parameters:

n -- the number to test for primality.

k -- the number of times to test for primality.

Returns:

True if n is probably prime, False if n is definitely composite.

"""

# Step 1: Handle simple cases

if n == 2 or n == 3:

return True

if n <= 1 or n % 2 == 0:

return False

# Step 2: Write n as 2^s * d

s, d = 0, n - 1

while d % 2 == 0:

d //= 2

s += 1

# Step 3: Witness loop

for _ in range(k):

a = random.randint(2, n - 2)

x = pow(a, d, n)

if x == 1 or x == n - 1:

continue

for _ in range(s - 1):

x = pow(x, 2, n)

if x == n - 1:

break

else: # This is a python trick which means this will trigger if the loop doesn't break

# n is definitely composite

return False

# n is probably prime

return True

You can check if a prime number \(p\) is a safe prime by checking if \(\dfrac{p - 1}{2}\) is also prime number. You can read the Wiki on why here, the TL;DR is that it helps you avoid prime factorisation with Pollard’s p − 1 algorithm.

Great so to get a 2048 bit key which is considered big enough to be secure we need to generate two 1024 bit odd numbers between \(2^{1023}\) and \(2^{1024} -1\) like the following:

\[\displaylines{ p = 141602569024907423239656383061960431859020441679714760968565115994745504511112193469709716260700701831247811066520007752058797131962782003724295718788292504481541198768955955731655532115577882986159162187790636793674308168795771701337429399728545829718038437990978063616486807345278549732188493288684634187923\\ q = 136227968310707046198839972829160415374259853869596809776780440815110959777505348078985651368827869672434072142427912233747209707613996143722500887828873757012431532403800390002631948204645695268807345547197790870911915368086912926008767466492463725910839247135205574711583019825075336577831742880088084711021 }\]Now as you can see these numbers don’t fit neatly into my blog so we are going to have to pick some smaller numbers that will allow us to do our equations neatly. We can call them \(p\) and \(q\).

\[p = 3, q = 11\]Our first step will be to calculate the product of \(p\) and \(q\) which we will call \(N\).

\[\displaylines{ N = p \times q\\ 33 = 3 \times 11 \\ }\]OK now the first bit interesting math happens, we need to find out how many numbers there are between \(1\) and \(N\) that do not share a factor with \(N\) greater than \(1\), we call this the totient of \(N\), or \(\varphi(N)\). This is really easy for a prime number, you can just take away 1 from the prime number since by definition it will not have any factors greater than 1. However \(N\) is not a prime number, but it turns out that if you multiply two totients together the result is the totient of the product. You can read more about this on the wiki page for Euler’s tonient function.

\[\displaylines{ N = p \times q\\ \varphi(N) = \varphi(p) \times \varphi(q) }\]So since we know that the totient of any prime number is one minus itself:

\[\displaylines{ p = 3, q = 11\\ \varphi(N) = \varphi(p) \times \varphi(q) = (p - 1) \times (q - 1) = 2 \times 10 = 20 }\]Now we can create a public key, first we need to pick an \(e\) such that:

\[1 < e < \varphi(N) \text{ and e and }\varphi(N) \text{ are coprime}\]We can just use 3 because it’s a prime number so it’s coprime with everything already, it’s less than 20 and it’s small which means it will be cheaper to encrypt things with it. Our public key becomes a combination of \(e\) and \(N\) or \((3, 33)\).

So the next part is the private key, we need to pick a value \(d\) such that

\[(d \times e)\bmod{\varphi(N)} = 1\]So we can use the Extended Euclidian Algorithm which looks like this in python

def extended_euclidean_algorithm(a, b):

if a == 0:

return (b, 0, 1)

else:

gcd, x, y = extended_euclidean_algorithm(b % a, a)

return (gcd, y - (b // a) * x, x)

We can call this like \(\text{extended_euclidean_algorithm}(e, \varphi(N))\)

That looks as follows with each call on the stack and the return value beside it as follows:

extended_euclidean_algorithm(3, 20) : (1, 7, -1)

extended_euclidean_algorithm(2, 3) : (1, -1, 1)

extended_euclidean_algorithm(1, 2) : (1, 1, 0)

extended_euclidean_algorithm(0, 1) : (1, 0, 1)

The final \(x\) value is \(7\) which we can use since as the value \(d\) since it satisfies the condition:

\[(7 \times 3)\bmod{20} = 21 \bmod{20} = 1\]We now have our private key which is the combination of \(d\) and \(N\) or \((7, 33)\)

Now we discard all the values except for our private key and public key, then we can give our the public key to everyone and hold onto our private key. Then if someone wanted to send us the message \(m\) they could transform it into \(c\), the encrypted version as follows:

\[\displaylines{ m = 4, e = 3, N = 33\\ m^e \bmod{N} = c\\ 4^3 \bmod{33} = 31 }\]Then if we want to decrypt this value we can do the same process but using \(d\) instead of \(e\), and \(c\) instead of \(m\).

\[\displaylines{ c = 31, d = 7, N = 33\\ c^d \bmod{N} = m\\ 31^7 \bmod{33} = 4 }\]We get the value back out, it’s not possible to get that value unless you can figure out the factors of N, and if N is a 2048 bit number that will take some time. You can also sign a message if you want to show it was definitely from you by using your private key to encrypt the message like so:

\[\displaylines{ m = 4, d = 7, N = 33\\ m^d \bmod{N} = c\\ 4^7 \bmod{33} = 16 }\]Then I can send a message to someone saying the message is 4, and the signature is 16. Then they can validate it as follows:

\[\displaylines{ c = 16, e = 3, N = 33\\ c^e \bmod{N} = m\\ 16^3 \bmod{33} = 4 }\]When you see a public or private key in RSA it typically looks something like:

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

AgEHAgEU

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

This is just the two numbers in a public/private key converted to ASN.1 Structure, DER Encoded and then Base64 encoded.